Chichén-Itzá

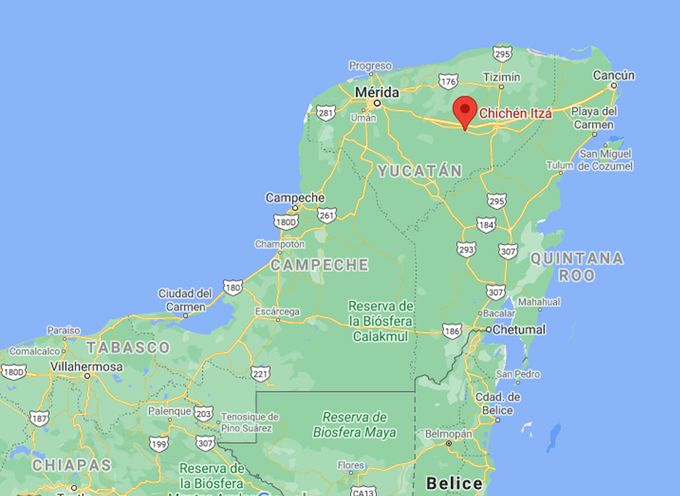

Chichén Itzá is a large archaeological site in what today is the municipality of Tinúm in the Mexican state of Yucatán.

The ancient city is also the engine of Yucatán’s

tourism industry, bringing in an average of well over one million visitors every year over the past couple of decades and over 2.6 million tourists in 2017 alone. Chichén Itzá is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and was declared one of the New 7

Wonders of the World from a selection of over 200 sites voted on by people across the world.

The name Chichén Itzá means “At the mouth of the well of the Itza” and is derived from the Yucatec-Mayan words chi, meaning mouth or maw, and ch’en meaning well. Itzá is the name of a distinct pre-Hispanic ethnic group that achieved political and economic dominance in the northern Yucatán Peninsula during the late terminal classic period sometime near the beginning of the second millennia.

The Water Wizards or Itzá are thought to have migrated to the Yucatán from the south. After the fall of their great cities including Chichén Itzá, Edzna, and Mayapan, it is believed that they returned

to their ancestral land on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá in modern Guatemala.

But the history of Chichén Itza dates way back well before the arrival of the Itzá, whose name is thought to mean “enchanted waters”

or “water wizards.”

Because Chichén Itzá has gone through so many phases of occupation and construction, the origins of the site are difficult to date precisely using archaeological methods. That being said, it is widely accepted

that the city first reached prominence sometime in the fifth century CE, and was likely permanently settled by Mayan peoples in the third or fourth century. Epigraphers of Mayan hieroglyphics suggest that before the arrival of the Itzá, Chichén

Itzá was known as Uuc Yabnal or Uuc Hab Nal, meaning Seven Great House or Seven Bushy Places respectively.

During this earlier period, the city would have been in competition with other important centers in the region including Yaxuná

and Cobá.

By the time Chichén Itzá reached the height of its power in the 11th or 12th century, it was one of the most diverse cities in all of Mesoamerica. The ancient metropolis attracted migrants and merchants from across the region

— a fact that is reflected in the city’s diverse architecture.

Remember when I mentioned that it was ironic that Chichén Itzá has become nearly synonymous with the Maya? Well, the thing is, Chichén Itzá’s

most iconic structures are not very “classic” Maya at all, but rather examples of Toltec architecture with a Mayan flair.

Now, it’s true that in past articles I have made reference to the influence of “non-Mayan” architectural

styles in other sites, but in Chichén Itzá, these influences are turned up to 11 on a scale of one to 10.

Now, this is not to say that Chichén Itzá is not really a Mayan site, just that it’s funny that structures like the Pyramid of Kukulcán and The Grand Ballcourt have become so closely identified with the Maya when in reality, they are great examples of amalgamation from across Mesoamerica.

The Pyramid of Kukulcán

The Pyramid of Kukulcán, also known as El Castillo, is a Mesoamerican step-pyramid standing 30 meters tall. As its name suggests, the pyramid was dedicated to the cult of the feathered serpent deity known as Kukulcán — who was closely related to Quetzalcoatl, a similar divine figure worshiped in central Mexico by peoples including the Aztec.

The versión of the temple visible today was a final iteration, with previous structures having been built over and used to house some truly fantastic artifacts inside interior chambers reachable through narrow passageways.

Out of concern for the integrity of the structure, access to these passageways has been prohibited, as has climbing the pyramid itself. Once in a while, someone will go ahead and climb the pyramid anyway, but it never goes well.

The pyramid is made of a series of square terraces with stairways up each of its four sides. At the top of the pyramid sits an imposing temple. As all four sides of the pyramid have 91 steps, when added together and including the temple at the top, their sum comes to 365, the number of days in the Mayan Haab calendar — and of course that of our own Gregorian calendar.

During the spring equinox, the sun strikes the northwest corner of the temple, creating the illusion of the descent of the feathered serpent in shadow form. This spectacle routinely attracts thousands of visitors, including new-age practitioners who believe the event has some kind of cosmic significance.

The Grand Ballcourt

This enormous complex is not just the largest of Chichén Itzá’s 13 known ballcourts, but the largest and best-preserved in all of Mesoamerica. The Ballcourt is delineated by two 95-meter-long parallel platforms that flank the main playing area.

These platforms stand at 8 meters and each has at its center a carved stone ring decorated with intertwined feathered serpents.

The platforms that have survived the ravages of times amazingly well feature several panels depicting the game itself, as well as its final outcome, human sacrifice.

Much has been written about the sacrificial element tied up with this “game.” Some have speculated that it was the captain of the winning team who was honorably sacrificed, while others argue that this grizzly outcome was afforded to the loser. It has also been suggested that this “sport” served as a proxy for warfare, or as a way to give an honorable end to noble captives.

The size of ballcourts varies widely across the Mayan world, and some did not use ringed markers at all, as was the case in Copán, Honduras. In most of the Mayan world, including Chichén Itzá, the ballgame was known as Pok ta Pok and

saw players strike a heavy ball with their hips (also possibly elbows and knees) through a large stone ring.

Behind the ballcourt, but built into the same structure, is the Temple of the Jaguar featuring a stone jaguar throne, similar but less adorned

than the one found inside the Temple of Kukulcán.

Ballcourts are not exclusive to the Mayan civilization, as a wide range of variants can be found across the ruins of several other cultures including the Totonac, Olmec, Aztec, and even those of peoples as far north as the Hohokam of Arizona. A more modern, less bloody, version of the game — ulama — is still played by the indigenous populations in several regions, notably Sinaloa.

Temple of a Thousand Warriors

This sprawling complex to the east of the Temple of Kukulcán is made up of a series of interconnected buildings and just over 200 stone columns (no, not quite one thousand) several of which are carved with images of Mayan warriors.

The largest structure in the complex sits atop a large artificial platform, featuring the reclined figure known as the Chacmool, flanked by two large columns resembling stone serpents. Unfortunately, it is no longer possible to climb this structure, so I would recommend viewing them with the aid of binoculars or a telephoto camera lens.

The Sacred Cenote

Though Chichén Itzá actually had several cenotes, the Grand or Sacred Cenote held special importance. According to some accounts, the people of Chichén Itzá believed this particular cenote to be the home of their rain good, Chaac. Inside the cenote, archaeologists have found thousands of objects including artifacts made out of gold, carved jade, copal, obsidian, and shell. The bones of men, women, and children have also been found inside the cenote, some of which appear to have had their hands or feet bound, suggesting ritual sacrifice. The cenote was also a place of pilgrimage for people from the region, and perhaps further afield.

Las Monjas

Las Monjas (The Nuns or the Nunnery) is a complex in the area known as the Central Group built in the Puuc style, which makes heavy use of elaborate rain god (Chaac) masks, especially on the ornate structure known as La Iglesia, or “The Church.”

The Observatory

The Observatory or Caracol is a round structure that sits atop an imposing rectangular platform, just to the north of Las Monjas. The structure is thought to have served as an astronomical observatory with doors and windows aligned to study astronomical events such as the path of Venus.

Other points of interest

Some other points of interest in Chichén Itzá include the Platform of Venus, House of the Metates, Casa Colorada, the Osario Pyramid, Akab Dizb, and La Casa del Venado. This is to say nothing of the countless structures still waiting to be restored in the surrounding jungle.

In early 2021, Mexico’s Institue of History and Anthropology announced that it will open a new section of Chichén

Itzá, commonly known as Chichén Viejo (or Old Chichén) to the public in 2022.

Though the existence of these structures has been well documented for decades, authorities have been hesitant to open them to the public, citing concerns

over their ability to adequately supervise large numbers of tourists over such an extensive area.

At nearby camps, hotels, and cenotes, such as Cenote Ikil, it is possible to make out large unrestored structures, likely belonging to Chichén Itzá’s periphery.

Other points of interest

Some other points of interest in Chichén Itzá include the Platform of Venus, House of the Metates, Casa Colorada, the Osario Pyramid, Akab Dizb, and La Casa del Venado. This is to say nothing of the countless structures still waiting to be restored in the surrounding jungle.

In early 2021, Mexico’s Institue of History and Anthropology announced that it will open a new section of Chichén Itzá, commonly known as Chichén Viejo (or Old Chichén) to the public in 2022.

Though the existence of these structures has been well documented for decades, authorities have been hesitant to open them to the public, citing concerns over their ability to adequately supervise large numbers of tourists over such an extensive area.

At nearby camps, hotels, and cenotes, such as Cenote Ikil, it is possible to make out large unrestored structures, likely belonging to Chichén Itzá’s periphery.

If you go

Getting to Chichén Itzá from anywhere in southeastern Mexico is easy as roads are generally good, parking is plentiful, and guided tours departing from Mérida, Valladolid, Cancún, and the Mayan Riviera are abundant.

The main downside of visiting the Chichén Itzá as part of a tour group, aside from the inflated cost, is that most tours only afford you a couple of hours at the sprawling archaeological site. If all you really want is to do is snap a few selfies and knock Chichén Itzá off your bucket list, this may suit you fine. On the other hand, if you really want to get the most out of the experience, you will need at least one full day.

Arrive at Chichén Itzá well before the gates open at 8 a.m. and avoid, at least for a while, the hordes of tourists which are sure to follow. If you decide to spend the night to get an early start or figure you will need an extra day, several options, at just about every price point, are available in the nearby town of Piste. At the entrance to the site, you will find clean bathrooms, spots to purchase water, and even a couple of restaurants.

Admittance to Chichén Itzá will cost you almost 550 pesos if you are a foreign citizen, and just under 250 if you are Mexican. Entrance to the site is free on Sundays from Mexican nationals and foreigners residing in Yucatán. Entrance fees are usually covered in organized tours, but make sure to ask just to make sure this is the case.

At the site, you will be approached by certified guides offering you tours of the ruins. The quality of these tours may vary depending on the guide but tend to be fairly good. Prices depend on the language in which you would like the tour to be offered. Most of the time you easily find guides offering tours in Spanish, English, French, German and Italian — though if you would like a tour in some other language such as Rusian or Chinese, you will want to book ahead.

Share this page